Any choice can be made, and framed, at any of these instances: as a resolved conclusion, as an insightful answer to mystery, as a response to urges and appetites, as a determination of proper (re)action, and as a consequence of feeling, welling up in the soul. For any artist, any aesthetic choice can occur in these conditions, depending on his or her built-up responses to life.

Or at least that is what appeared to me today after ploughing through different exhibits from three different museums in the city.

Taiyo Kimura and Kong Vollak were my companions today as we set on a day of museum visits that included The Whitney Museum of American Art, The Bronx Museum for the Arts and the Jewish Museum. Taiyo suggested Whitney and The Jewish Museum because he wanted to see the works of Robert Irwin and Jack Goldstein, respectively. I suggested the Bronx because of Bronx Calling, the second AIM Biennial. And also because I have never ventured into The Bronx as a borough, not within the four months I have been in New York. We ended the evening in a Japanese drinking hole in St Marks Place, at the insistence of Vollak.

We were at the Whitney at opening time and surveyed all five floors top to bottom, for its permanent and temporary exhibits. So from the fifth floor we went through the survey of the American modernists - Hopper, O'Keefe, Nadelle, Davis - a journey that continued with an exhibition of Hopper's Drawings (on the 3rd) which I really, really liked. At the fourth level, Taiyo and I were stunned by the "Veil" by Robert Irwin which was a site-specific work for the Whitney and since its first exhibit in 1977 has not been shown in 35 years. Taiyo told me that Irwin, a Light and Space artist, was working within the same parameters as did James Turell whose show at the Guggenheim we also saw together two weeks ago. I understood why Taiyo wanted to see this piece, as I myself was astounded by its sheer simplicity and yet its magnificent presence. The use of a translucent screen to catch the light of a single window and allow it to skim gradually along its surface to a point (but presumably not end) of the far side of the wall is an astounding work of insightfulness and keen observation. If Irwin wanted to elicit wonder, he got that from me. But it was his framed statements about art "going beyond making" that made me shrug my shoulders. The work was enough, but his contrapuntal statements - perhaps needed to make discursive space for himself in the art politics of his period - were already superfluous.

It is quite odd actually for me to discern the same deliberateness of Irwin in the drawings of Hopper. Edward Hopper is an old favorite of mine and whose exhibition in Paris was ongoing at the Grand Palais while I was there last year. (I deferred going to the show because I knew I was going to see Hoppers in the US in a few months. This exhibition did not disappoint that choice.) The collection shows studies and various works on paper by Hopper, given context by the presentation of the very same paintings that were the results of these sketches. So while I finally found myself standing in front of "Night Hawks", I was privileged to see the drawing he made to make this. Imagine my surprise to see notes on his drawings, and annotations in his journals and logbooks that indicate precise placements of tone and shade at every part of the composition. Hopper saw to it that nothing was out of place and yet his painterly approach to his canvases remain fresh and without any sense of belaboring.

At the lower floors we saw the remounting of works by American artists from the 80's and 90's - from Kiki Smith, Keith Haring to Jean-Michel Basquiat - as a throwback to current issues of their day: AIDS, Reagan foreign policy, gay rights etc. While viewing the show it came to me that I have never been very acquainted with the history of American artists after World War 2. And this lack of information had contributed to my attitude towards post-modern American art in general. Quite curious how a simple survey, a simple viewing can change what I thought about these works. How did I ever even fall into this aesthetic bigotry in the first place? I mean, I love Kiki Smith. I found the works of Irwin, Goldstein and Turell very profound.

My education was incomplete, as my judgment of contemporary art and its antecedents in the 70's to the 90's is flawed from the lack of concrete information.

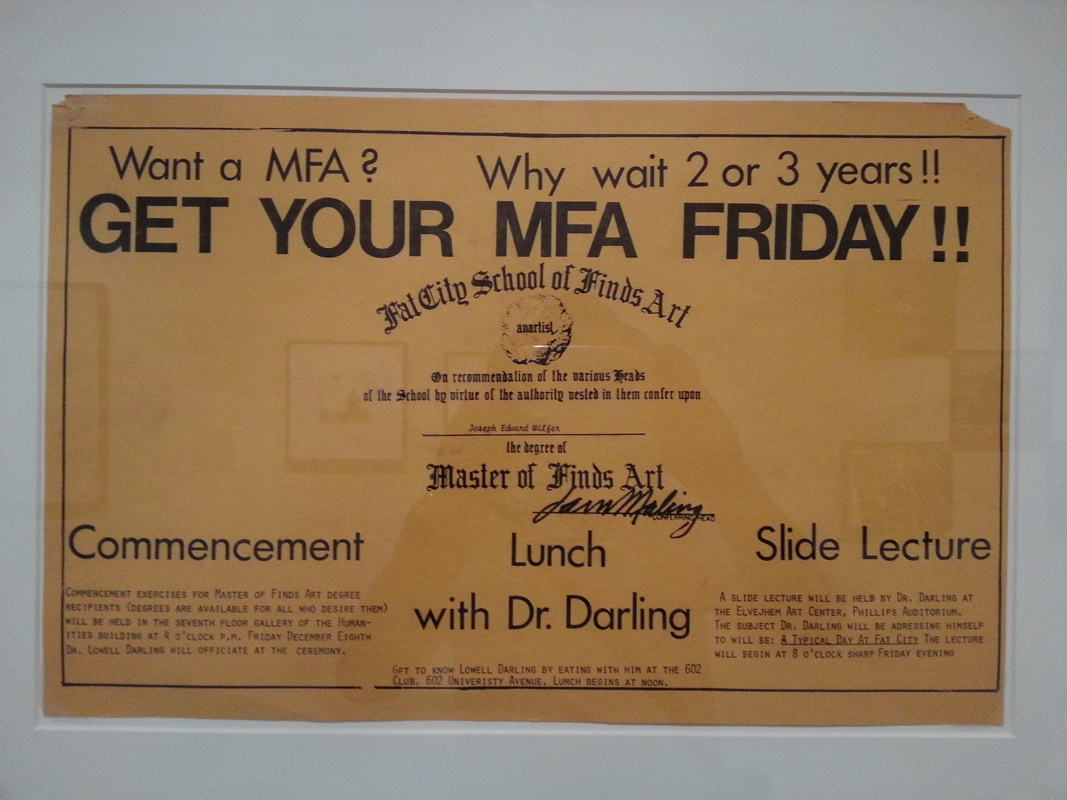

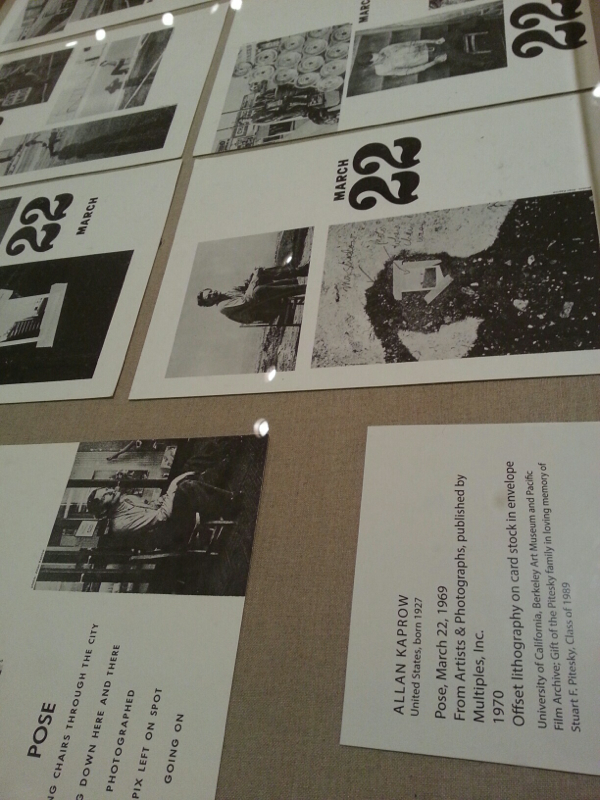

So it came as a bonus and a surprise for all of us when we discovered that a survey of West Coast art from the '70s was on show -for free- at the Bronx Museum. Taiyo was particularly amused as he did want to see a show like this. The exhibit was for me a way to confront and engage the West-Coast variety of conceptual art, language-based art, new media etc. Months before I would have reacted aggressively against seeing works like these. To my amazement, after weeks of concluding my personal experiment (see previous entries) the works actually appeared amusing. I loved the sense of irony, the courage to explore the boundaries of language and image and to audacious mockery of "traditions" and institutions. I was very drawn to the video of John Baldessari's performance where he was singing off-tune the postulations of Sol Lewitt: it was just too funny. I even found the book art of Ed Ruscha and Allan Kaprow arresting in their interest to map out immediate environs and gestures in their place. The show made me consider that aspect of observed phenomena of the "present" as a string of passing impressions and recordings.

Somehow, the AIM Biennial paled in comparison to this retrospective show. I could not help but think the contemporary works were just "following through" the explorations of the past four decades, in terms of form and modalities of practice. What is markedly different in the contemporary works is the regard for concrete situations - immediate history, revisionist politics, geo-cultural manifestations - that seem to be lost in the explorations of form, and in the reaches of semiotic art of the 70's.

The retrospective of Jack Goldstein's work at the Jewish Museum was a fitting end to the unfolding of the day. In fact I enjoyed all of his short films, which were quite properly projected using the same projection machines of his day. It was his late paintings that I found a bit off, although his use of flat planes of acrylic and the conscripting of assistants to do these for him (to remove himself as an author and assert his position as a director) were thought-provoking. But of course, someone like myself who takes pride in worksmanship and skill naturally would be estranged by this attitude. It did not prevent me, though, from giggling at his films, especially the one where a page of text is hurriedly read because it was rapidly being burned from top to bottom.

So as a rejoinder of my opening statement, I do say here that different artists call for different causes and different modalities are called in for different sets of concerns. There is no question of legitimacy here (which is a loaded question premised on lineage and institution), but rather of contextualization.

Looking forward to more.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed