I call it "truth of the pavement", this habit of mine of trying to understand a place by walking its streets. By no simple effort does Manhattan reveal itself on a single promenade. I have never walked a city this big before; the mere fact that by standing in the middle of 3rd Avenue I cannot see both the north and south ends of the road always daunts me. But I have resolved to understand this city with my feet: bring on the pain.

Although I have been in the arts practice since I was 18, and have functioned in various roles in its world, I cannot but admit that I am now just beginning to understand my own creative processes. Each project, each artwork is a process of self-understanding, or even a manifestation, an aletheia of something that had hitherto been occluded from my own awareness. In effect each work comes to me as a surprise because Ive never had to anticipate the final structure of the work, nor draw its full form. I pay attention to the insights proffered and prompted to me as a result of a visual, emotional and even extra-sensory stimuli. And these stimuli I often discover in the act of exploring, traveling, and at the most basic level, by walking.

I now know that even with the most rational, most logical and most conceptually compelling project that I can conceive in my head, my creative process seems to take another path and like jazz, takes on a more improvisational manner. With the last Open Studios at LMCC Art Center, I had an insight to rearrange the whole installation a few hours before the start of the event simply because of an insight I received while aboard the Coursen ferry. Looking at the works that I have made during the past weeks, I discover that none of my planned works have ever materialized in full: the works finish themselves through a series of last-minute alterations.

It is as if the true author of my work, the artist behind the pieces, is a doppelgänger. In Ilocano, we call this a Kadkaduwa, literally the double soul that lives side-by-side in another dimension, as opposed to the Western Anima, that is the ghost in the shell.

Also, I even suspect that I am being led by this double, this kadkaduwa, to places that I have never been even remotely interested in. Its like I am being led by a headstrong dog on a walk in the park. It is only by a tug on the leash, my tempering of reason, that keeps me within the confines of the pavement.

Today I found myself looking for the White Horse Tavern in Greenwich Village and the parade grounds of Washington Square Park. I know for a fact that Dylan Thomas had collapsed (and died shortly) after a drinking binge at the Tavern in 1953. It was this that drew me there, this scent of a passing. At Washington Square, the stately old trees were once used to hang people in the 1700's. I sought solace there, in what appears to be a streak of morose mood swings. Yesterday I sniffed out the place where John Lennon was shot at the Dakota. Then walking along Bleecker, Christopher and Washington Place streets, I espied the historic buildings and noted how residual memories and presences are impressed on the faded details of architectural decor. It seems that my dog of a doppelgänger has led me on a ghost hunting tour, and the truth of the pavement may very well be espying haunts in the brownstones.

Can I hypothesize that my creative practice is a form of mediumship? I work to discover further, as I do feel sometimes that I am never alone.

White Horse Tavern. Where Dylan Thomas drank his last whiskey.

Washinton Square Park Arch. Marcel Duchamp once broke into this structure and declared Greenwich Village as an independent republic for and of bohemians.

Signage at Washington Square Park

I woke up today with the blues. I have been working straight two weeks since the exhibition at Bliss (last June 1st) and have not stopped until today. Thus I gave myself a mental cleaning and took a walk on a nice summer afternoon in the Upper Westside and in Roosevelt Avenue in Queens. I lingered over Strawberry Fields and stared at The Dakota and thought of John Lennon who was shot near the spot where I stood. Quite weird: all the subway singers were singing Beatles songs today, including a man on the 7 Train from Queens who sang "Yesterday" from Queensboro Plaza to Vernon Avenue. So: John Lennon is haunting me. (So I downloaded a Best of the Beatles album from Amazon's Cloud Player).

Also gave me an opportunity to draw freely while on the subway, which I have been doing since I arrived here. I was so interested on how the subway movement intervenes with my rendering of objects and people that are within my immediate environs. I shall call these collection of sketchbooks "Train of Thought".

Although I did take a break several times to clear my head, like the visit to the Open Studio event at NARS in Brooklyn where there was a preview of works and artists talks by Taiyo Kimura and Takeshi Ikeda (with the special participation of Kong Vollak), ACC grantees all. I found Taiyo's and Takeshi's works very engaging in their sense of humor. It was a very refreshing feeling considering that contemporary art pieces often seem sullen and catastrophic. It seems like everyone here is obsessed with an impeding zombie apocalypse of some sort - a changeover from infatuation with vampires and werewolves. Taiyo's concern with exploring social psychology provoked me to think of the public as well. In the solipsistic world of personal dreams where my work often lies, the gap between the work and the public is problematic.

Then there was Figment, a "participatory art" festival held last weekend at Governor's Island. I went there on a Sunday because the rains kept Saturday a bit apprehensive. Despite the hordes of people (not comfortable with crowds) that came in by boatloads to the Island I was able to thoroughly enjoy the event. Most of the works on site were a bit corny, some really badly constructed. What stood out for me was this fascinating construction called "Head in the Clouds", a large sculpture made out of recycled plastic milk containers, set on the open grounds of the island, near Fort Jay. More impressive was the fact that a DJ was playing some house music inside the structure. Gave me the impression of a beehive. The mini-golf works were charming, as children and some adults did try them out - despite there were more obstacles than range.

The rain has proven to be quite the obstacle for me these past two weeks. Manhattan does not look well under a storm cloud, as does the ferry ride to and fro Governor's Island. So most of my work is continued in my apartment in Midtown, especially detail work that does not involve mallet strikes. Also, I finally got weary of the tedious commute and the difficulty of stopping work before 6pm, the time when the Island closes to the public, and the ferry ceases to operate. I learned to take my work back to the apartment everyday, lugging almost 20 pounds of wood and tools each way. But when Sandra, in a meeting with other ACC grantees, explained that this was really how New York based artists work - because they live far from their studios (rent issue) - I learned to understand, almost viscerally and physically, what artmaking means in this environment.

The sheer physical, financial and mental stress can make any artist living in the Bronx and working in studios in far Brooklyn reconsider making art that is object and craft-based. One of the artists at LMCC, Ethiopia-born Ezra Wube who lives in Brooklyn, told me of how he got rid of all his paintings that cluttered his living space and settled with a single canvas which he paints over and over again, taking still shots frame by frame and producing short animation videos from the progression of the work, which he projects onto the blanked-out canvas during an exhibition. During the Open Studios last May he showed me a flash drive where his work, he says, is all stored. That was an ingenious, remarkable and quite apt strategy for environments like New York, or other megapolises. I ask: why is this modality of creative processes then taken up by bourgeois artists in Manila and shown in white-box galleries and framed by essays peppered by quotes from Rosalind Kraus? Even as concept-, process- and project-based art are creative solutions used by the marginalized here versus the instituted notions of high art, why is that these are presented as objects of bourgeois consumption back home? My theory of traffic of novelty applies here: where a brick from New York, once transported to Manila, becomes regarded as an artifact of civilization. We are really far away from the Capital...but artists in Manila are not as impoverished as they claim...

Indeed what I can consider as a discovered gem of experience during the past three months of this residency is this: a sense of unburdening.

In the Philippine vernacular the colloquialism "bagahe" (or simply mental baggage) for artists is the sense of insecurity and an attendant sense of unreality that accompanies creative practice that is a) pontificated by institutions and a learned class and b) evangelized by textbooks, second-hand art magazines (often ten years old), and borrowed art books often Taschen publications that have little discourse and more plates and c) sustained by cheap China-made art supplies. In other words, art is something that is so conceptually intangible, as lofty as a Biblical parable and as complex as election politics: a very muddy yet cinematic paradise.

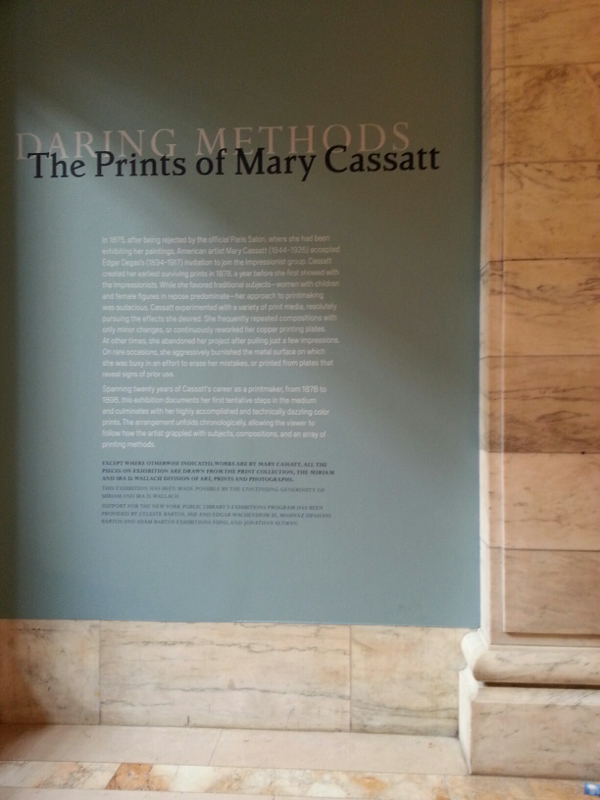

I came to Paris and New York, unknowingly carrying the weight of this insecurity. And eventually by living among peers and other artists - and also coming to witness the original works that I studied only from badly-developed slides and reproductions -I came to understand the ground truth of practice: often the frames are far too large for the art itself. To take off the baggage I had to dismantle the frames, the theories, the books, the words and the politics so I can face the work with a clear mind. So I can confront the work, naked eye gazing at a naked construct. In Buddhism the call this prajna, or the practice of non-attached awareness.

I am partial to experiential knowledge: I defer truth until I have come close enough to smell information. New York, Manhattan, Contemporary Art - these are no longer concepts for me. They have texture, they have weight and they have different scents to them now.

And so, I am learning to unpack the bags, and hopefully by the end of next month when I conclude my stay here, I can just leave these - like any New Yorker - on the curb with all the trash. Fit for dogs to piss and mark their spots.

Strawberry Fields, a memorial to John Lennon at West Central Park

Head in the Clouds. Made of recycled milk bottles. Figment Art Festival, June 9, 2013, Governor's Isalnd.

NARS Open Studios: Artist Talk

Taiyo Kimura's works at his studio at NARS, Brooklyn

I've just finished with the details of my very first complete sculpture here during my residency. It felt good that it came on the last few days of May, barely a week after the open studios at Governor's Island and a few days since my wife left for home. I have an exhibit opening on Saturday, June 1st, and I will be supplementing, no, replacing the main object of the show with this one that Ive just finished. Perhaps it was the combined emotions of anxiety to make a new work, of the sense of affirmation from responses to my work in the Studio, and of the feeling of being alone again after my wife left that I felt compelled to accomplish something. In my world that means making an artwork, a sculpture. It feels good to possess that sense of release and relief after all that struggle within and without. I mean, I have again a few scars - but its just another day at the office for a woodcarver like me.

It is hot in New York: the mercury says 90F. Still a little cooler than summer in Manila, but it was warm enough for me to go out walking in flipflops and shorts along 2nd Avenue. It felt strange as several weeks ago I was shivering from the same streets and now, with the warm sun easing my muscles, I feel quite at home. I am a child of the Sun, after all. I always long for the enchantment of summer.

The sculpture now sits on top of the writing desk at the foot of my bed. Ive placed a lamp on it for illumination and in the dark it looks like a sentinel. Ive used leather for the first time with this work, and like all my processes I discovered it by accident. Thus the work "flowed" effortlessly and constructed itself, guided by decisions and promptings of someone within or beside me. When I make works this way (with unseen guidance) I know my work is "right". How can I explain this? As an art history writer I can identify several artists and traditions that use this method. I am only beginning to understand this process, and it feels like something of either a haunting or a possession, or if Ilocanos have it, a communication between one's alteregos from other planes. Or other universes in hyperspace?

With regards to art and any cultural artifact, it is often not the form that is potentially problematic and suspect but the theoretical framework from which it is encoded at its infancy. Form flows seamlessly in the plenitude of things and objects and worlds. But framework is constantly riddled by the insularity of its codes, the limits of its theoretical horizons and conceptual range and ignorance. Consider that we live now, no longer in a mere "international" contemporary that is buttressed and buffered by transactions between discreet communities and nations, no not anymore.

We situate ourselves more or less, in a projected hyperspace of the "global", where connections and the means of connections are in place, and the metropolises being the nodes of these various nexus. We actually speak less now of geopolitical states in cultural dialogue (except the politicians and consulates); it is not just France, but Paris or Sete etc., not merely the US but in NYC, or LA, or San Francisco, nor just Thailand but Bangkok, not Korea but Seoul, nor just Indonesia but Jakarta, or not The Philippines instead we speak of Manila, or Cebu. The metropolis represents our point of departure to the global community that increasingly making its way through elsewhere. I predict that in the coming decades, once the metropolis has expanded its role from node to central gateway, those beyond the city shall become the next frontier. So that its no longer Tokyo, but also Ibaraki or Kanagawa; not just New York but also Brooklyn, or Manhattan; not just Bangkok, also Chiang Mai...more and more into non-urban sites, then finally into the realms of the sub-communities.

---

These thoughts came to me while looking at the diverse sets of objects in the exhibit "Connecting Communities: The World in Brooklyn" at the Main hall of the Brooklyn Museum yesterday. By putting together different objects from different cultures and periods under the themes of person, community and things, this exhibit made me rethink the network of the global and contemporary as the result of exposure, or presentation as interface. Consider that communities in the 20th century industrial pre-linked world were discrete lives lived in pockets of diaspora, ghetto and migrant neighborhoods, set beside established communities of colonial or native population. In the time of the internet and social media, all of these pockets become linked by virtual cities by means of a flat interface and a search engine. The dominant social theme is one of home and comparison, at least for the beginning. Then as these communities influence the infrastructure of the cities (app-directed transits, courier by web etc, cyberlinked libraries) we shall learn to speak of sub-communes, or trans-national affiliations: a post-international world. I found the exhibit prescient of this projection of a future, by being a showcase of accumulated objects from across many lanes of nostalgia and history.

---

Yet again, at the center of all these objects the concept of sculptural form is no longer urgent. Sculpture is but one of the many categories of objects, this one created under the auspices of Art. Sculpture intends to be of a higher construct, seemingly unconstrained by external forces of market and value, created for the pure sense of aesthetic judgment. But is it? These times call for a sense of reevaluation of claims.

---

In effect, the one cultural artifact that seems to stand with curious interest is the "story". In a global world punctuated by shades of differences, origins, allegiances (soon to be blurred in distant future of homogeneity) what matters is the story behind author, creation, artifact, structure, community, nation. Cultural communication is simply the exchange of stories. For what purpose? For many purposes, above all things is to provide information and persuasion of tolerance.

---

The exhibit, Connecting Communities, is a very good example of how stories however different can be grouped in many ways around a theme or place. Nicolas Bouriaud and Roger McDonald both thought of curatorial work as the DJaying of art, and that the exhibition can be seen as a Playlist or Album. This approach is a curator's way of dominating the traffic of art by discursive conglomerations and by subjugating the authorship of the artist. I think rather that the contemporary is best served, like in the case of the Brooklyn exhibit, as an anthology of stories, where curatorial direction is that of an editor, or more likely, an archivist.

---

There will be a time when the art world will be served more by archivists that curators.

---

Thus I conclude:

(1)The difference between object-based work and concept-driven production in art is the urgency of speed and delivery. It takes time and dedication to a stable concept that makes labor on making objects slower, than the sense of urgency that is needed to identify, collect and compact the idea into a form in a haste that mirrors the speed of conceptual manifestation.

(2) The object and the concept are BOTH iterations of storytelling. What is to be considered here is who do we think we are telling the stories to and how can it be repackaged for such audiences (translation, adaptation, even censorship).

(3) Contemporary is construed as a null-field where there lies the space for contending with projection (interpretations and digestions of past, like nostalgia) and trajectory (the direction towards the fulfillment of our visions, passions, appetites and debts).

(4) The global is hyperspace.

A yellow school bus served as a the shuttle from the Guggenheim Museum to the Frieze Art Fair on Randall's Island. As we made our way under the RFK Bridge and into the Randall Island Park I espied the large red inflatable rabbit sculpture of Paul Mc Carthy looming over the tent structure that held the Fair. I remembered what Freddie Aquilizan used to tell us: If you cant make it good, make it big. Quoted from Audrey Flack, who added if you cant make it big, make it red. This sculpture is both big and red.

Then suddenly we were hollered down by a group of men chanting "Shame on YOU!" as we made through the dirt road to the south entrance. The men - presumably artists with a cause - were waiting to pounce on the arriving guests with slogans and a funny inflatable rat sculpture with greedy eyes on their guard. All the guests in the bus peered back. The rat nodded with the wind. It was a fine Friday mid-morning, with 70 degrees on the mercury and sunny.

I wanted to make the most out of this visit and I planned to stay the whole afternoon if I had to. When I was doing the rounds of the Armory Show week I was reeling from jetlag, as I had barely a day upon landing. In contrast to the cloudy, grey and snowy late winter weather at the Armory, the near-summer heat of the day for Frieze was very, very welcome. Yet I keep telling myself: Oh God, another art fair! Ive been to many art fairs since last year, from Art Singapore, ArtHK12, FIAC and Slick in Paris, Art Fair Philippines, The Armory Show and now Frieze and pretty soon, Pulse and others. Everytime I go I think: this is a marketplace, and yet it is also a marketplace for ideas. What good was an artist if he could not capture the hearts and minds of people? Often the art fair is a shortcut to gallery hopping. Not quite the real thing, but it saves you some blisters.

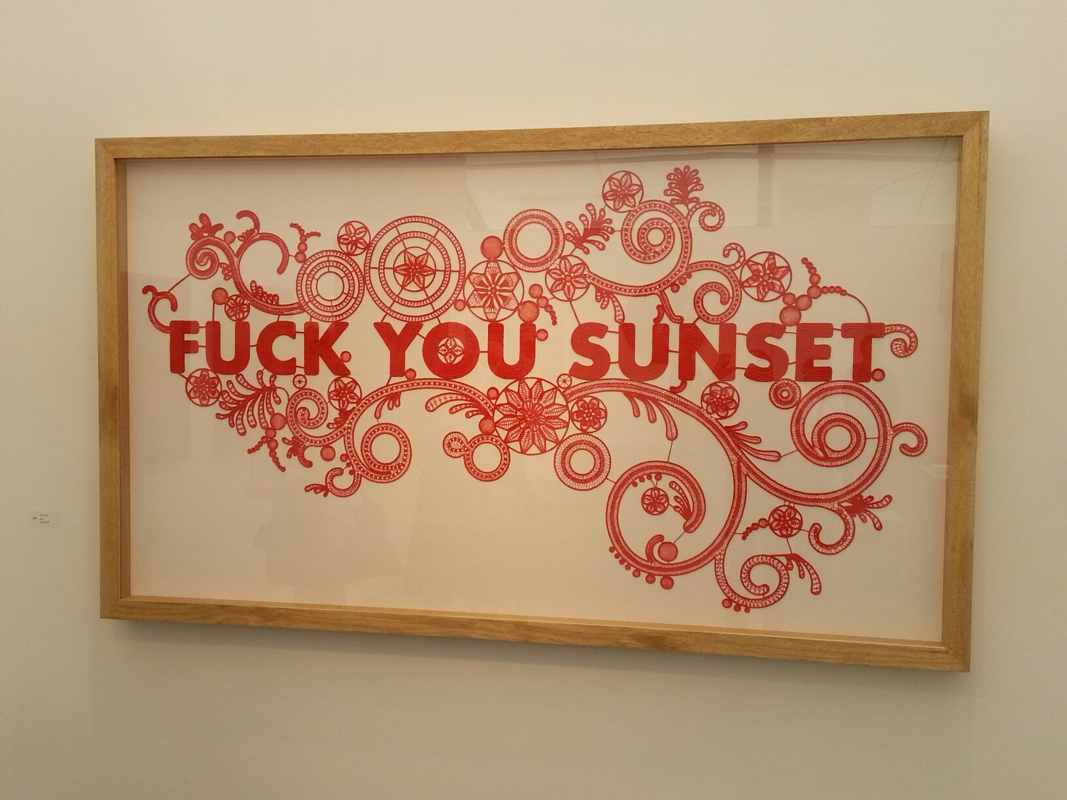

There is something about this edition of Frieze that made me chuckle and smile, the same way I found myself entertained at FIAC last fall. I stumbled upon the oxygen of contemporary art practice: permissibility. Or what can art do when we are given no limits nor laws nor canons. Or our lack of awareness thereof. Or the dismissiveness of all fetters and meanings and traditions that accompany these assertiveness.

I also came to terms with the context of lifeworld in comparing Frieze New York to all the art fairs elsewhere: here in these white spaces, are objects that come from living in post-industrial cities. Elsewhere in the City are two art fairs of "indigenous and tribal art" (which I am curious to see), where art from "beyond the city and beyond modern civilization" have their own limelight. Michel Foucault once said that history which is prevalent is the narrative of the powerful. In our time the meaning of being contemporary is evidence of mastery of narratives coming from the metropolises. Contemporary art is not about the tales of bunions, unless of course, they are assimilated into the heart of the city and its politics. What made me snigger and giggle at the Fair was the dawning of an understanding. It was not about the dichotomy of "craft versus concept" or "tradition versus contemporary" or even "West versus East"; these are the concerns of Cold-War period art.

Its ALL about the traffic of novelty, this global force driving contemporary international art.

Take an banal object from New York and bring it to Ilocos and suddenly it becomes a relic of a sophisticated civilization. Take a common trifle from Ilocos and bring it to New York and in the right context it becomes an exotic object from a distant land. City and country mouse tales. But this is nothing new. In the early modern and late 19th century, in the age of expositions, this was the operative force in showcases and impresario spectacles. What made the difference? The level of seriousness levied upon the funding, politics, and presentation of the exhibits. C'mon, these things are finely tuned, and finely crafted to make it speak with the deep baritone seriousness of Habermasian discourse. So funny. And they have magazines and websites to support the works that are so flimsy without the support of a whole encyclopedia of written words. Hahaha.

What else is hilarious? The presumption that the tales of the city mouse is richer and better than the yarns of the country mouse. Foucauldian logic: the world and the community that has more power has more leverage to say what history is better said, and everything else are footnotes. But what I find fascinating is the way the country mouse is also driven to find its hole and home in the Big City and have his tale also told in the spaces, however within the liminal; or else this country mouse picks up a thing or two and goes back home with the learining of the city and in the law of traffic of novelty, becomes famous.

Two days ago I received a premonition of death, which I thought referred to my own. I was sitting on a hillock in Central Park, basting in a warm slow sun watching birds and some sailboats at the Conservatory of Water when it happened. I thought of my grandfather and my father - both had died before they were 60 (55 in fact) - and made the logical conclusion that their descendant (meaning, me) is drawn a similar fate. I always have these thoughts of death whenever I feel the advent of something new. something changing.

Today I heard of the passing of Roberto Chabet, 76, a pioneering conceptual artist, who while childless, through his mentorship and dedication to his students, is a father to young generations of likeminded mavericks. Many of these artists-children are my peers, classmates and friends. Yet he was not my teacher; I have deliberately chose not to, in 1996. I shifted to another course, in Art History, just to evade being "educated" in what I thought back then was a faddish fascination for second-hand Art in America and ArtNews gospels of "what art should be". I was during that period studying under another great mentor, also another Roberto, the curator Bobi Valenzuela, and with him I was critical of anything of art that didn't consider being "Filipino" first, and foremost.

In an essay I wrote for a workshop in Jakarta in 2006 I compared the styles and values of these two Robertos-as-curators. Bobi had told me that while people had pitted him with Chabet he said he had no quarrel with "Bobby". He was a curator he really admired since his methodology was charged as a provocateur, tossing ideas and letting his students and then his artists to figure out how to respond. I was so pleased when this essay was in fact, copy-pasted by Sir Chabet in his Facebook account, some years ago. It was an event that punctuated many years of recovering from a misunderstanding of the man and the artist.

The first episode of realization came when Sir Chabet, during an exhibit opening, described a project he was thinking of, a film or a video art piece that would be about Chiquito, a FIlipino comedian popular in the 70's. Then he spoke at length, even with relished enjoyment, about Chiquito, which was to my surprise uncannily uncharacteristic of someone accused of dragging Warhol and Duchamp into the halls of UP Diliman, and forcing conceptual art to its starving, fishball-and-buko juice fed fine arts students. This man was misunderstood; I misunderstood him. He knew his roots, but was not constrained by the need to assert it. Instead he found routes into creative practice that was beyond the canvas, the figure, the palette and the brush, and even the constructs of nationality and locality. Chabet had provoked innovative ways to think of ideas that were not "theatrical", nor just "symbolic". In other words, he made his students and his viewers think out of the confines of their own baggages, and out into the freest of creative ether: into humor, sly, rebellious sardonic humor. Art that was even unconstrained by market forces, although his younger students would become one day prove quite financially successful.

Thus inasmuch as my current practice was forged in a different persuasion - one that affirmed the primacy of craft over concept, and the authenticity of vernacular identity over cosmopolitan homogeneity - I also credit Sir Chabet of having shaped my aesthetics, all so indirectly, a dialectic presence that tested my faith and my nerves. In the end what defines an artist's resolve and mettle is not the differences of aesthetic values, the valences of commitment to causes and concerns outside art, nor the clique where one can identify his blood-brothers, comrades, fellows and peers. It is the sense of being enamored to the creative life and vision, and the persistence of living within this sentiment, often to use one's existence as a means for the re-enchantment of the everyday, the banal and the ordinary...so that they can attain the nature of the extraordinary. Sir Chabet did that in his art and in his generous mentorship. I hope to find the same relentless fire that he had. A fire that can be passed on, a Promethean fire, a clarifying flame.

Provoke the heavens, Sir. It would be unlike you to rest and be still. Impart your spirit to the universe: so we can find irony and humor in every molecule.

Another day of sharing my work at the Studio, this time among other artists of Swing Space: Karl Erikson, Kimberly Ruth, Jamie Diamond, Elisabeth Smolarz and Ezra Wube. Two days ago it was the curators Amara Antilla and Lyn Hsieh from the Guggenheim who went to the Island to talk and see my works in progress. There is a kind of fulfillment in these artist talks: a sense of being able to gauge one's work through the responses of others, especially peers. These two studio visits brought a lot of positive things: first by making the presentation I am able to articulate my practice and second by noting reactions I was able to find resonances in creative endeavors - although we do not belong to the same genre or field, or even aesthetics. It was one thing to show (off) the final works at an exhibition, but also another thing to be able to show the process and be given input on other artists' strategies and projects.

I spoke with Ezra as we both made our way to the ferry docks. He is Ethiopian and had settled in the US since college. He is a painter, a process-based painter who is quite curious about documenting and preserving transience by gestural memory. In a way his work becomes a palimpsest, painted, erased, painted over and his efforts are documented on video and he hopes to have these videos projected on the finished canvases, as echoes of the process. I was quite intrigued about his stories of Ethiopia, its original form of Christianity centered on Axum, and how the art scene there has just picked up abstraction, and how this "belated" sense of modernism has some awkward dynamics in the way art is made and presented there. The last bit about modernism struck home: as a writer on art history I am aware of such moments in Philippine Modern Art, when the Filipino early pioneers pussyfooted with "distortion" at first but quickly found their own unique visual language, whose points of departures and references were usually one or two modern master, but mostly, Picasso.

Long Island-born artist Jamie Diamond's presentation of her work the Reborn subculture was also intriguing. Her studio is the first one that I pass by when I enter Building 110 and her shelves full of life-like newborn dolls and photographs of such made me wonder what was going on. Reborn was featured (quite badly) in a BBC program called "My Fake Baby" and it is an exclusive group of women who make, adorn, and exchange these life-like dolls of vinyl and silicon among a community. Some of the members of this group have experienced a loss of a child and it would be reasonable for them to adopt this practice as a coping mechanism. Yet some are also fertile females who do not have children of their own, and some, like Jamie, are artists interested in making them. Jamie had to find her way into the community for some time and now she is working with some of them, as there are those also wary of her presence.

What I like about her project is that it reminds me of Simon Flores' portrait of the dead child, a genre known in the 19th century as recuerdos de patay. Her work and her very autobiographical approach and sense of communal involvement is very contemporary, also even a bit resonant of the relational aesthetic that I have been suspicious of. I think of my work and I see, in the context of contemporary practice and construct, do I see possibilities of presentation, project planning and framing. I am using the theoretical framework that was indeed so 80's. Its not the practice nor the work that seems deficient and insecure: it is merely finding a way of communicating my intentions to the artistic community that is, by now, quite global.

When it was my time to present my work I did so first by explaining where the Philippines is and where Ilocos is and how these are not just factors of my creative practice, but in a sense, a ground from which I emerged as an artist. In preparing this presentation late into the night and early morning, I found out how much my training as an art history student in fact informs how I choose my subjects, my techniques and formulate projects. Inasmuch as I want to say I am no longer a curator or an art historian because I am now an artist is in reality, a false declaration. Because my interest in the rebulto is not merely artistic, it is also and most importantly a practice of connoisseurship: I cannot but help use research as part of my methodology. What I do reject and criticize is not historian but the speculative critic and theorist. I still maintain that art is not about applications of theory: it is not some praxis. Theory emerges as a manner of making sense the production of the work. What I criticize about curators is their stance of directing or stage-handling art history with the notorious concept of "intervention". They are the proverbial cart that wishes to be in front of the horse. The again I have to think of curator as a role and not a position (something I picked up in 2006 in the Multifaceted Curator Workshop in Jakarta).

I am actually happy to realize this as it somehow eases an internal tension of identity. Somehow posing as a "simple woodcarver" is a very, very bad way of articulating my practice and is bad faith.

So we begin with what are true statements.

My interest in the rebulto is an outcome of connoisseurship training and resonance. I love old stuff, I love history and I love traces of history. This was perhaps formed because of Ilocos, of Vigan: I was never a city boy. I am always drawn to historical objects and historical narratives. I am always curious how history, the past, or the recollected and vestigial past reminds us of our own lifeworld trajectory. I am interested in the cause-effect relationships, of then and now, the continuum therefore of narratives that bridge personal and even generational lifetimes. I love the genealogy of the graven object.

In military science there is a folly called "fighting the last war", where the general adopts strategies that were successful in a previous war but catastrophic in applications to a present conflict. If I had not gone on these artist residencies, and have not decided to engage my work in the Asian region, I would have been still "fighting the last war" in a Cold War scenario of neocolonial and post-industrial ideologies. The game is different now in the sense that a conceptual ground of practice is laid out globally and artists, working from their own cultural, personal, relational and historical backgrounds can move in to play and there is discourse here.

If an artist wants to the work to connect, then he has to ultimately engage artistic communities with some sense of participation. In a way that is what contemporary art practice is: a sense of connectivity, of empathy and even, of advocacy. In a previous entry I discussed the importance of location, or knowing where your ground is. Location is referentiality, something that you can identify as your origin or home base. Now I also understand the sense of community (having something in common) and connection, in a way of engagement. Like Jamie's Reborn subculture or Ezra's diasporic Ethiopia, every artist identifies the community he or she is wholeheartedly involved in. Because in that way art is not just a matter of wanton self-expression, but a genuine motion, a human gesture, of sharing.

Works in progress at the studio.

Carving tools at the studio...well some of them. I still work on the floor, Asian style.

I am trying out a new paradigm - and with it new ways of making works - that has been coalescing in the background of my thoughts ever since I started these extended residencies in Europe and now in North America.

This is a paradigm of queries rather than theses. Because now I find myself full of questions, mostly probing verity of stated and assumed facts. And ironically, these are statements that I may have made, but also have clung closely for about two decades.

It started in Paris, where confronted with the images of the Old World I found myself beaming, "Oh so this is what this really looks like". I was, in fact, describing my encounters with all the artworks and structures that Ive only seen in my art history books. Talk about living in a "precession of the simulacra", as most of us find ourselves in Third World and web communities. The goal, or the dream you might, of say of those whose lives were peppered by images and reproductions, is to find passage to see the "original". (A journey often construed as pilgrimage, as I have described it in my last exhibition Curator of Pilgrimage and Paid Vacations, at the Drawing Room last month) So while the "original" work or object is not within our tactile or visceral reality, we live with its emanations and iterations, so to speak. I have written about this on the Mona Lisa experience, where when finally face-to-face with Da Vinci's work I was deeply, er, let down: it was dim, it was small, and it was hard to look at without being elbowed by other spectators. I guess I could say the same with Bartholdi's Lady Liberty, the icon of New York if not the US. But unlike the La Gioconda, I have not the privilege of going to her up close: I am reserving that on my final days. Meanwhile I simply watch her at the same distance every day from the ferry to and from Governor's Island.

Ad so I am all in askance: what observable phenomena can be considered to make this assumption, true? In short, how do I know I am not being duped, or I am not deluding myself? It all goes with: who told you that? what are the sources? And even: Can I just continue with the ruse, as I am anyway having a good time?

---

For close to two decades I have been taught (and unfortunately even taught it elsewhere) with the following theses:

You are a Filipino first before being an artist.

As a Filipino you inherit the task of defining yourself from the gambit of neocolonialism and the colonial constructs of 300 years of Hispanic domination. Likewise you are put to the task of resisting the neocolonial powers that are in ascendancy.

As a Filipino artist it is your task to edify local culture, identity and history: in other words, dig deep and find that core.

There is, sometime in the past, a great civilization of pre-Hispanic Filipinos that was destroyed and assumed by the Spanish colonial masters and churchmen.

Only then, in touching base with these, that you can create authentically. Those idiots who make art for art's sake are just potheads, addicted to neocolonial hash.

Believe it or not, I held on to these theses like a credo. It did not help that I worked as a consultant for a government agency, National Commission for Culture and the Arts.

Then I began to ask:

Why does cultural identity have to be "pure"?

Why look for something archaic, even utopian, and prefer this OVER the present?

Why does cultural research, identity politics take precedence over art practice? Who said so?

Why reject colonial heritage? Aren't these part of one's culture? AND

Why can't I provoke, propose, pioneer cultural introductions and insertions...as a creator?

And finally...seriously...can't I have fun?

---

I used to think that cultural identity is a matter of assertion. You claim identity, you post it to a community.

But culture, being an artefact of communal life of dynamic shared language, idioms, norms, values and habits, has a tendency to become rigid, once it has been demarcated. Like a stray hen that you try to pin down in a certain territory, you place a fence or a coop around it. Thus, here culture becomes a construct, a mental object, a thesis supported or supplemented by objects - in other words, a marketable idea.

And it pains me to find out, in hindsight, that I bought into the whole cultural paradigm when it was in fact more a hindrance to me as an artist. Its like patronizing a really bad barbershop, and you won't know the service is totally messed up not until you try the other shops elsewhere. I didn't know. I didn't have sufficient information. I didn't have sufficient comparative experiences.

---

Patrick Flores has a phrase that I really love: "Preaching to the choir". Its like "converting the faithful" or "selling to the distributor". An ironic redundancy...so thus, have I been really working with irrelevant themes and practice...or am I just preaching to the choir? Time to turn around and face the congregation? Or the people outside the church?

April 20, 2013

I have never appreciated being in New York as much as today.

Three reasons:

Spring

Central Park

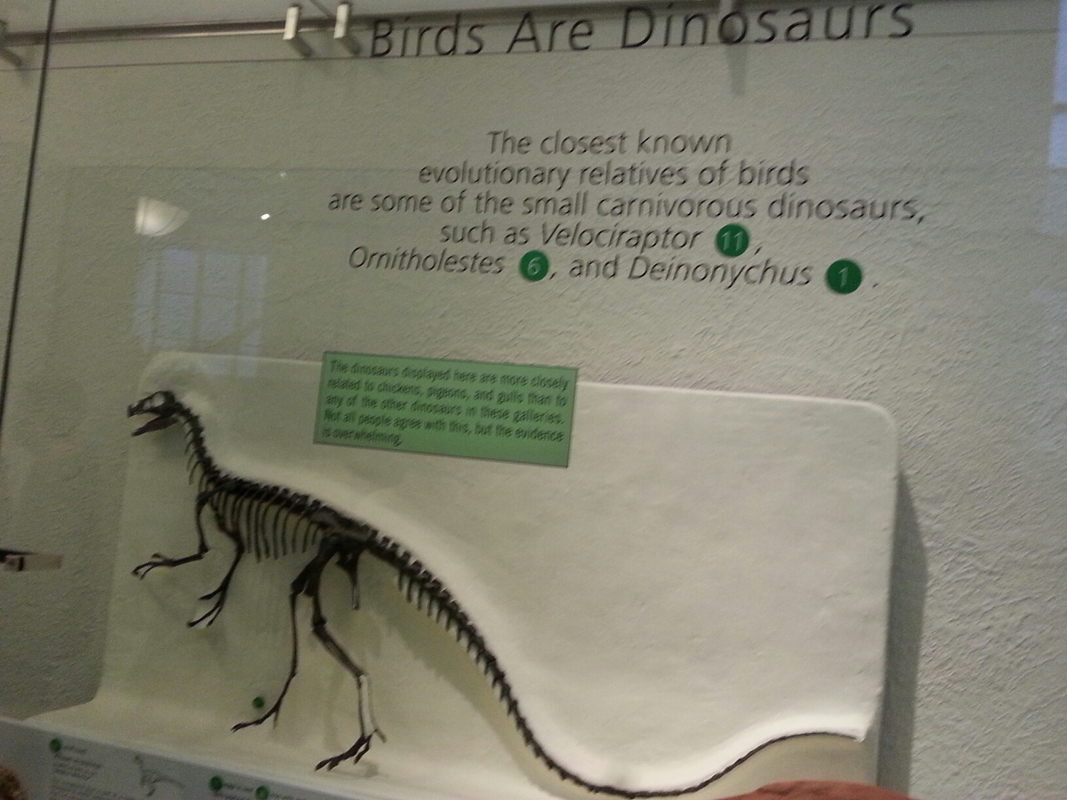

and The American Natural History Museum

I spent the whole day actually enjoying all three.

The common denominator of experience is wonder at nature. Environments, ecosystems as as subject have never failed to elicit awe and curiosity in me. For the record this is my firsthand experience of spring. And it is quite good to have New York associated with this memory, for this will be the kernel of a whole complex of associations of experiences and memories of succeeding springtime. The sun felt good, the air is warmer and breathable, and the sight of people lolling about, running, playing on the lawn of Central Park was just remarkable. The last time I was in the Park it snowed! I took the 6 train uptown to 77th st and walked from the Met Museum through the Park to the Natural History Museum, passing through the Belvedere Castle. And seeing families enjoying themselves made me appreciate the day even more.

I spent six straight hours in the Museum, having gone through all its permanent collections and seeing its 40minute show at the Hayden Planetarium. And I still had a hour's worth of walking from the West side of the Museum to East 44th: to digest the experience.

I realized that instead of making statements, I was better (and more authentic) in asking questions. In a way, I felt that majority of my life projects revolved around queries and inquiries. And that the regions of my interests (within which I ask a lot) are the following:

Cosmological/Mythological (The Universe,speculations in scientific and religious pictures of "the whole")

Ecological and geo-biological (The body, The earth as us as iterations of the organic and inorganic)

Historico-cultural (Societies, norms, shared habits, language and symbolic language)

Relational-social (Others, relationships, intersubjective communication)

Personal: History and Lifeworld Trajectories (The Unconscious, Personal prehistory and trajectory)

Consciousness (Phenomenology and Zen)

The American Museum of Natural History offered me the chance to get curious in three of the six regions of interest.

Lunar rock!

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed