Sculptors know this: that it takes more than a photograph or a drawing to aid in rendering the plastic qualities of a work. In seeking references the sculptor must be physically present to his model. Otherwise the sense of solidity (or its displacement) evades him and the work is doomed to a contrivance of dimensions. This is the case of Baroque-styled santos in the Philippines, where often the wood carver was given a print to copy and he faithfully reproduces that - and results in nothing but a raised projection of a design. (A connoisseur in antiques once deplored the lack of articulated back parts of Ilocano santos, perhaps the references have no design for rear parts?)

As I needed this sense of solidity, I went to look at the works of a true modern master sculptor at the eponymous Musée Rodin in rue de Varenne. And I was not disappointed but in fact overwhelmed. Housed in a beautiful mansion and the artists former home, Hotel Biron, are Rodin's works in bronze, plaster and marble, including his studies, maquettes and other works by friends and assistants. The museum however is under renovation and some parts of the garden are even walled off. Yet the 9€ entrance fee grants you access to all areas including the temporary exhibits. (You have access to everything, says the cashier in English).

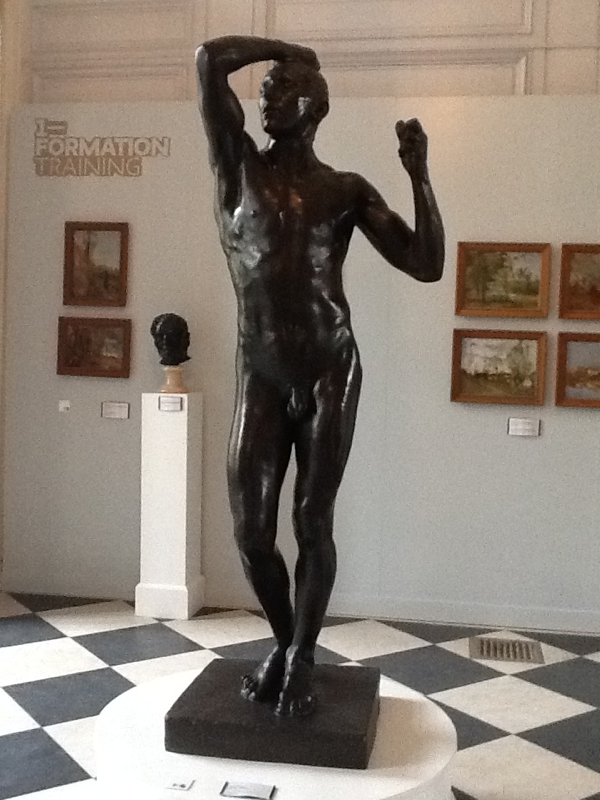

Auguste Rodin lived from 1840 to 1917. He was hailed even during his lifetime as an ingenious innovator of the classical sculptural form whose tradition goes as far back as the Greeks in the 5th century. While decidedly academic and classical in his use of materials of stone and bronze and the depiction of the human figure as subject, Rodin's mastery of clay modeling allowed him to present the body in elongated and contorted poses that results in emphatic and expressionistic overtones that defined his body of work. There is something poetic in the way the sculptor handles mass, and his approach is almost improvisational. He defines bodies like mountains, with muscles and sinews erupting from the form, like a volcano seeping through. The primary clay whose malleable dollops are preserved in bronze, retain the viscous quality of having one slapped over the other. There lies the vigor of a Rodin work: its sense of immediacy.

As I was looking forward to studying Rodin's works intently, I went about the sculpture garden unhurriedly. I was also delighted to have some morning sunlight, although it was veiled by the low-lying clouds. In the garden are some of his well known works: The Burghers of Calais (which I used as a reference in my thesis in 1994), the Gates of Hell and The Thinker. In the museum itself the works are temporarily arranged chronologically from one room to the next. It begins with a presentation of Rodins early works, including forays into Impressionist painting. Then the exhibit goes on, from showcases of busts, maquettes and studies to casts of important works such as his versions of the Monument to Balzac. One room is devoted to the works of his friends, apprentices and his muse, Camille Claudel. This room has a few paintings including an oil by Edvard Munch, a Renoir nude and a seascape by Monet.

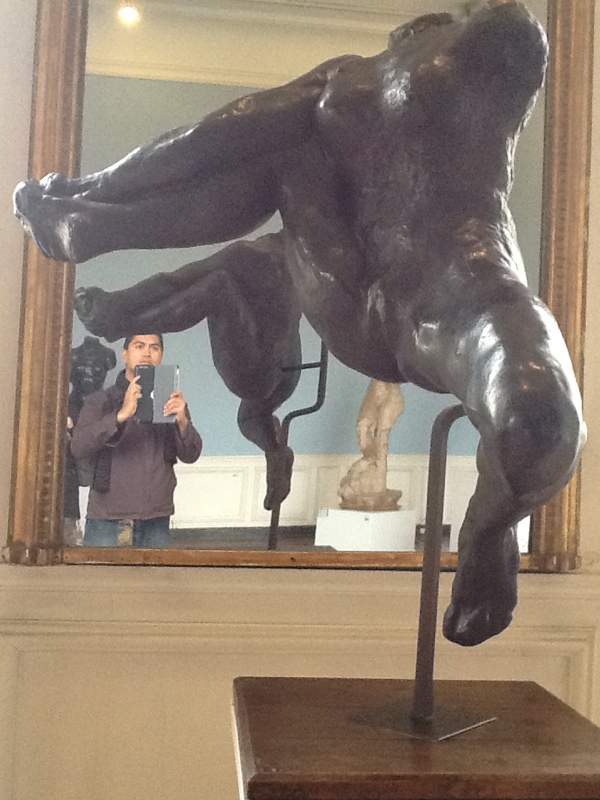

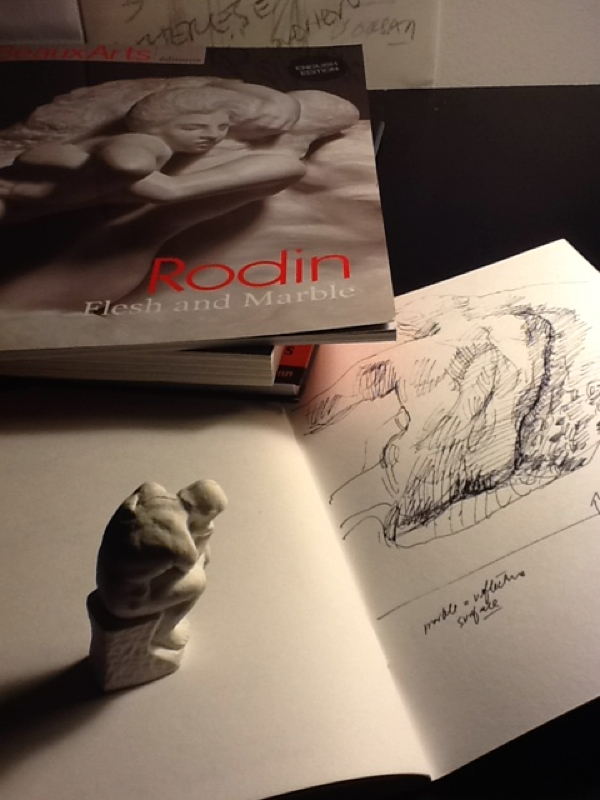

At the last room at the second floor I decided to set aside my Ipad and dis some sketches in order to discover the solids that comprise the forms of his nudes and the work, Iris. But it was in the special exhibit Rodin:Flesh and Marble that really made me analyze the master's approach to form. Although there are only a few that Rodin did work on directly, most of the marbles were done in collaboration with stone carvers and apprentices.

What seems to be Rodin's real guide is the play of light and shadow, or tones. He utilizes recessed areas to create dramatic darks from an overhead light, and often in these penumbral space he articulates details less. With marble, especially in his masterwork, Thought, he also uses the capacity of the surface to reflect light. With Thought (La Pensee), the unworked block of stone catches a downstream light and bounces off gently on the face (that of Claudel). Careful articulations of eyes and nostrils allow the light to define some of these details. Rodin was a keen master of the theatrics of light on material...astounding. From Rodin I learned that the form often follows the definition of dark and light, and the poetics of his contortions are highlighted by the presence of sweeping swathes of beautiful shadows. Michelangelo discovered that sculpture is also a matter of focus and emphasis, like in the case of painting. Rodin extended this idea by using polished and rough textures, finished and unfinished parts, illumined and darkened areas to complement each other and provide the eye a proper perspective on how to regard a work in the round. A sculpture is not the summary of different angles of interest (not a 360 degree painting!) but rests on one primary viewpoint with the rest and details supporting that view.

You'd have to be standing in front of a Rodin to see that angle, that vantage point that he gives emphasis, because the work emanates from that spot.

So was I able to apply these things at work today?

No.

I had to take the whole day off, to be able to digest the visual feast that I am currently engorged with.

As I needed this sense of solidity, I went to look at the works of a true modern master sculptor at the eponymous Musée Rodin in rue de Varenne. And I was not disappointed but in fact overwhelmed. Housed in a beautiful mansion and the artists former home, Hotel Biron, are Rodin's works in bronze, plaster and marble, including his studies, maquettes and other works by friends and assistants. The museum however is under renovation and some parts of the garden are even walled off. Yet the 9€ entrance fee grants you access to all areas including the temporary exhibits. (You have access to everything, says the cashier in English).

Auguste Rodin lived from 1840 to 1917. He was hailed even during his lifetime as an ingenious innovator of the classical sculptural form whose tradition goes as far back as the Greeks in the 5th century. While decidedly academic and classical in his use of materials of stone and bronze and the depiction of the human figure as subject, Rodin's mastery of clay modeling allowed him to present the body in elongated and contorted poses that results in emphatic and expressionistic overtones that defined his body of work. There is something poetic in the way the sculptor handles mass, and his approach is almost improvisational. He defines bodies like mountains, with muscles and sinews erupting from the form, like a volcano seeping through. The primary clay whose malleable dollops are preserved in bronze, retain the viscous quality of having one slapped over the other. There lies the vigor of a Rodin work: its sense of immediacy.

As I was looking forward to studying Rodin's works intently, I went about the sculpture garden unhurriedly. I was also delighted to have some morning sunlight, although it was veiled by the low-lying clouds. In the garden are some of his well known works: The Burghers of Calais (which I used as a reference in my thesis in 1994), the Gates of Hell and The Thinker. In the museum itself the works are temporarily arranged chronologically from one room to the next. It begins with a presentation of Rodins early works, including forays into Impressionist painting. Then the exhibit goes on, from showcases of busts, maquettes and studies to casts of important works such as his versions of the Monument to Balzac. One room is devoted to the works of his friends, apprentices and his muse, Camille Claudel. This room has a few paintings including an oil by Edvard Munch, a Renoir nude and a seascape by Monet.

At the last room at the second floor I decided to set aside my Ipad and dis some sketches in order to discover the solids that comprise the forms of his nudes and the work, Iris. But it was in the special exhibit Rodin:Flesh and Marble that really made me analyze the master's approach to form. Although there are only a few that Rodin did work on directly, most of the marbles were done in collaboration with stone carvers and apprentices.

What seems to be Rodin's real guide is the play of light and shadow, or tones. He utilizes recessed areas to create dramatic darks from an overhead light, and often in these penumbral space he articulates details less. With marble, especially in his masterwork, Thought, he also uses the capacity of the surface to reflect light. With Thought (La Pensee), the unworked block of stone catches a downstream light and bounces off gently on the face (that of Claudel). Careful articulations of eyes and nostrils allow the light to define some of these details. Rodin was a keen master of the theatrics of light on material...astounding. From Rodin I learned that the form often follows the definition of dark and light, and the poetics of his contortions are highlighted by the presence of sweeping swathes of beautiful shadows. Michelangelo discovered that sculpture is also a matter of focus and emphasis, like in the case of painting. Rodin extended this idea by using polished and rough textures, finished and unfinished parts, illumined and darkened areas to complement each other and provide the eye a proper perspective on how to regard a work in the round. A sculpture is not the summary of different angles of interest (not a 360 degree painting!) but rests on one primary viewpoint with the rest and details supporting that view.

You'd have to be standing in front of a Rodin to see that angle, that vantage point that he gives emphasis, because the work emanates from that spot.

So was I able to apply these things at work today?

No.

I had to take the whole day off, to be able to digest the visual feast that I am currently engorged with.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed