I thought of giving each week a theme upon which all my activities would emanate from. This idea came to me after I've realized that I was looking at Paris as a curator and not as an artist. Not that a curator's perspective is insufficient, but I wanted to respond to my time here aesthetically, with emphasis on immediacy. I wanted this residency to unfold around creative ideas in response to the environment, and hopefully not turn into some post-college field trip, where I felt impelled to see the originals of what my textbooks and references have shown me as examples of art. My goal is to develop a body of work from the experience of "being in Paris" and not "about Paris". I already gave this creative a title: "You cannot step into the Seine River twice" Perhaps this is can be a future name for a show, or a name of a piece.

This weeks theme is Death. Morbid, agreed, but this simply means a weeklong visit to a number of sites where the dead are interred, honored or given prominence in terms of edifices and structures. This covered churches and crypts, cemeteries, ossuaries and civic buildings and monuments. I wondered how the dead are remembered in Paris, and how the afterlife is constructed and how legacy or heritage is built around the memory of the fallen, and the departed in concrete form. I wanted to compare this with those I know of in Manila and elsewhere in Asia. (I was informed of late that the Museum Foundation of the Philippines is also doing a similar tour of tombs in Manila. It might interest them that I have actually stumbled upon the sepulcher of Pardo de Tavera in Pere Lachaise.)

I began my tour with looking for one of the last remaining cemeteries in Paris, Cimetiere Charonne, that was allowed to operate even after the government decided, for sanitation reasons, to move the remains of then overflowing graves to an underground ossuary, now the Catacombes, in 1786. I discovered that it remains to be a simple plot of graves, dotted by sepulchers on a hillside beside a small church. The only point of interest here is a bronze sculpture of a house painter, purported to be the confidante of Robespierre, although a website denounces this as untrue and nothing more than a posthumous prank.

Being nearer to where I was I took the Metro to Pere Lachaise and spent time looking for tombs of people whose works I admire. Thanks to a map I downloaded online and the interesting fact that there are good wifi hotspots in cemeteries (future grantees take note), I was able to maneuver around the vast hilly area with its remarkable mix of sepulchers, mausoleums and funerary sculptures from the 19th century. Thus I found the graves of the painter Gericault (with an effigy and reliefs portraying his best known works such as The Raft of the Medusa), Chopin (with an angel on top and a medallion in marble of his profile), the artist Arman, the poet Victor Noire and his famous bronze effigy (depicting a fallen young man with a curious erectile bump that visitors have worn off by touching), Amedeo Modigliani and his wife Jeanne (the latter committing suicide the day after his death and lastly, out of curiosity, Jim Morrison, of The Doors. On my way out, I discovered the sepulcher of Trinidad Pardo de Tavera, a prominent scholar of Philippine history and culture.

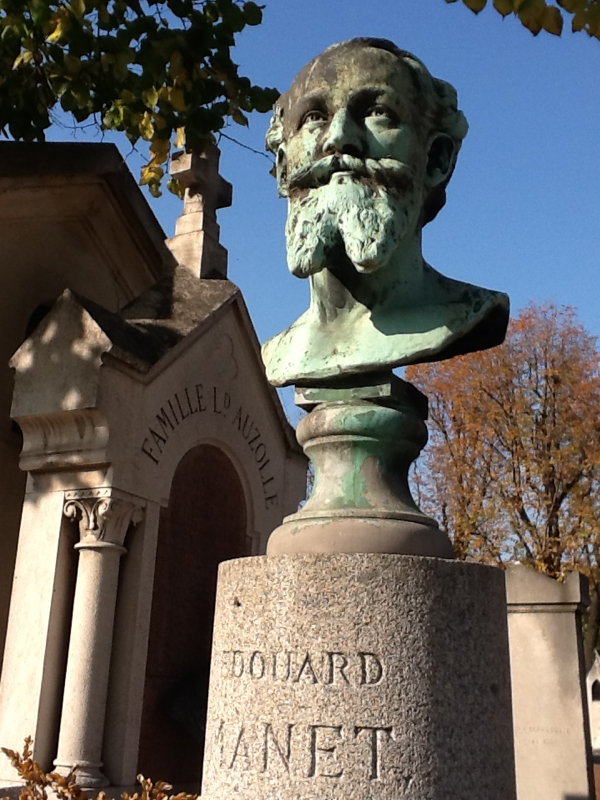

The following day I struggled to find Cimeterie Picpus, the site of mass graves of the 1300 victims of the guillotine but found it closed. Frustrated, I went to three others, Montmartre, St. Vincent and Passy where I spent some hours for the rest of the day. At Montmartre I paid my respects at the tombs of Degas and Dumas (shown with an effigy of the writer in repose, sadly damaged). This cemetery has a number of very interesting funerary statuary that I could not but take photographs. Wifi was so good near the sepulcher of Degas that I was able to talk on video via Skype to Jun Villalon, gallerist of Drawing Room in Manila and Singapore. When he saw where I was, he commented that I was making a pilgrimage. Probably so but not inaccurate. At nearby St. Vincent, under the shadow of the dome of Sacre Coeur, I found the tomb of painter Maurice Utrillo. Then later than day I took the Metro to Trocadero and found the graves of Manet and Debussy in Cimetiere Passy. This small cemetery also had very interesting sculptures, among which are a bronze Rodin portrait and a St Jeane that was remarkable for its sensuous form, despite the context of a holy place. But what moved me as a sculptor was the massive wall sculptural group commemorating the French soldiers of the First World War of 1914-1918. Their austere forms understated the pathos of grief and remembrance, and highlighted the sense of tragic dutifulness - of the burden of going to war. Ironically the players of this Grande Guerre were in fact initially cheerful, as they brought their idealism and youth to the front, only to be destroyed by the dreary trenches and experimental use of chemical weapons and tanks. It reminded me of a young French sculptor, Henri Gaudier-Brezska, who fought and died during this war, but not without losing his sense of aesthetic as he carved small sculptures in stone during the intervals of non-combat. He fought the war with sculptures in his pockets. A brilliant life, and indeed he was called a Savage Messiah by HS Ede, a British writer who did his biography.

I continued my Dead week theme with a return to Montparnasse on Thursday and a much-delayed visit to Basilique St. Denis the day after. In Montparnasse I again passed by the grave of Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir and found the tomb of Brancusi. I took photographs once more of numerous statues and began a comparative listing of characteristics from each cemetery. This cemetery for instance has a Nikki de St.Phalle sculpture of a giant cat in tiles and concrete and another abstract metal piece representing a bird in flight, in contrast to the Romantic bronzes that show weeping women in shrouds and with Baroque overtones of glorious afterlives.

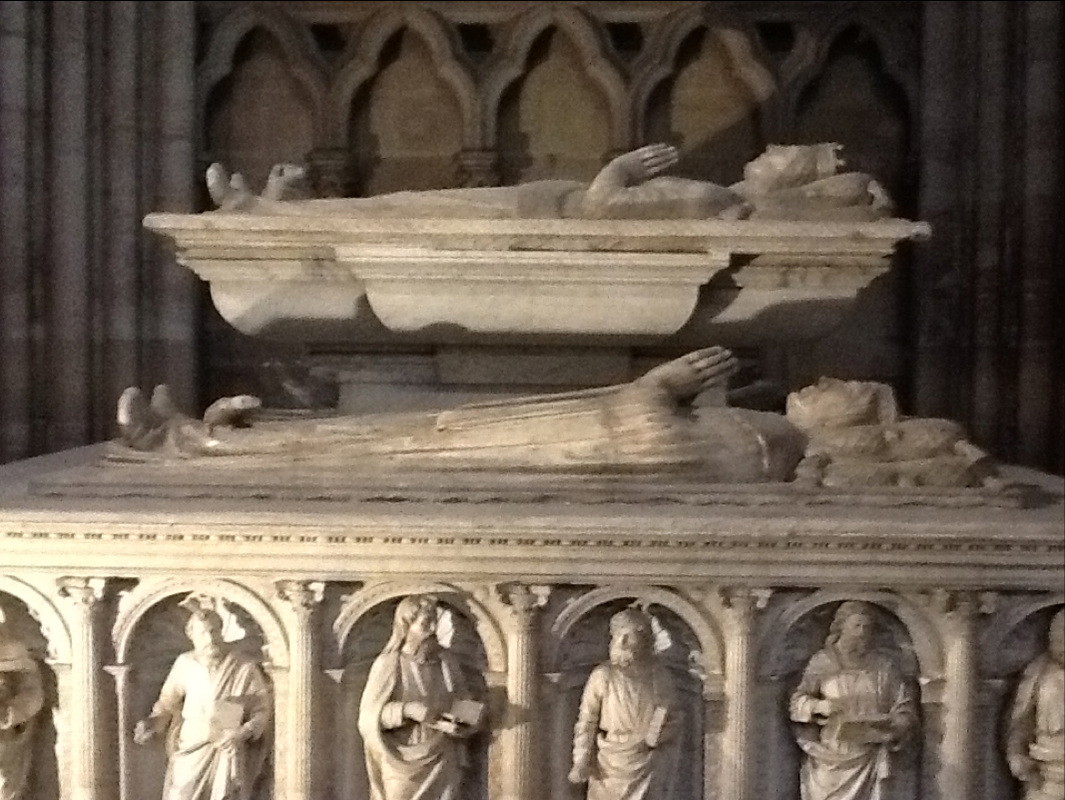

At St. Denis, at the crypt and before the stone effigies of the Kings, I found the acme of my week. At the rear of the huge basilica (accessible with a ticket of 7,50€) lies a number of carved representations of the dead royals, mostly in marble, eternally resting with their eyes gazing upwards, and often carrying their symbols of power. But I explored the crypt first, which houses the tomb of St. Denis, claimed to be the first archbishop of Paris and martyred (beheaded) around 250AD. Being trained in santo-making I was quite taken with the representation of this martyr: dressed in a bishops garment, but with his decapitated head in his hands. One reproduction of a painting even presented him with blood squirting from his severed jugulars. But what was remarkable to know was this site was a pilgrimage place since the 5th century and was one of the most powerful Benedictine abbeys in the Middle Ages. It became a necropolis of kings and queens from the 6th century onwards. In the 12 century Abbot Suger of Saint Denis made the former abbey into an example of early Gothic art, but it was in the12th century that the church received its present look and after deteriorating through wars and the revolution it was restored by Viollet-le-Duc in the 19th century. If I may comment, I have not seen any church this ancient back home.

In the crypt I found the tomb of St. Denis, the symbolic center of this basilica, and met some French school children being regaled by a wiry teacher with stories of how St. Genevieve, patroness of Paris, had asked Hannibal to spare the city. The tomb, of carved stone, lies empty, but a projected image of the saint marks where his body lies underground (a nice solution by way of signage) and surrounding this area are more sarcophagi, but beyond a grate and gate and inaccessible to all. In the adjacent areas lies other crypts where princes and kings where once interred.

Emerging from the crypt and into the necropolis were the stained-glass illuminated chapels that held around 70 recumbent statues of the royals. I was attracted to a particular chapel, named in honor of a St.Hilaire. With my santomakers hagiography I have not encountered such a saint before, an a namesake at that.

What I paid close attention to are the sculptures, taking photos of interesting details, such as the way hair is carved, or what animals are placed at the feet of the kings, mostly dogs. One unknown royal was curiously carved in black stone and at her feet are three snarling dragons. While doing documentation I had an insight, a confirmation of a suspicion really, that the models and prototypes that my santero uncle had shown me when I was 15 were of the Gothic style. And it was this style that I preferred over Baroque or Neoclassical santos (which I thought were a bit superfluous). The austere, block like and linear forms of the funeral statuary of this necropolis echoed those of my own aesthetic sensibilities. In fact, I began to wonder if this is my very own "French connection". Here, in the context of a medieval building, I began to understand the origin of the images that were my models of instruction in wood carving. The ancestry of my sculptural practice may really be the Gothic, and hence my attraction to the arts of the Medieval period.

Hence, in conclusion to my Dead week, I have gained several insights and this thematic approach has somewhat given much-needed coherence to my exploration of Paris. I have learned a great deal about the changing attitude of the French towards the dead: from the open eyed statues of the kings at St. Denis as a way of looking upward in anticipation of Eternal Life, to the eternal postures of grief of funeral statuary in Pere Lachaise, to the simple, understated tombs of great men like Sartre and Brancusi bearing nothing except names.

Sartre has said in one of his stories that death is a wall. There is nothing behind it, nor one should even care what is beyond this. But death does not belong to the moribund, to the dying. It belongs as a fact, to those who left behind. Simone de Beauvoir eulogized the passing of her life long partner Sartre by saying "his death separates us, but my death will not reunite us." She was right, though. Our lives might be within the horizon of our freedom, but when we have left, our death will only have meaning if and when those who survive us, remember.

And that is what cemeteries, necropolises, ossuaries and monuments are for: an effort to remember.

This weeks theme is Death. Morbid, agreed, but this simply means a weeklong visit to a number of sites where the dead are interred, honored or given prominence in terms of edifices and structures. This covered churches and crypts, cemeteries, ossuaries and civic buildings and monuments. I wondered how the dead are remembered in Paris, and how the afterlife is constructed and how legacy or heritage is built around the memory of the fallen, and the departed in concrete form. I wanted to compare this with those I know of in Manila and elsewhere in Asia. (I was informed of late that the Museum Foundation of the Philippines is also doing a similar tour of tombs in Manila. It might interest them that I have actually stumbled upon the sepulcher of Pardo de Tavera in Pere Lachaise.)

I began my tour with looking for one of the last remaining cemeteries in Paris, Cimetiere Charonne, that was allowed to operate even after the government decided, for sanitation reasons, to move the remains of then overflowing graves to an underground ossuary, now the Catacombes, in 1786. I discovered that it remains to be a simple plot of graves, dotted by sepulchers on a hillside beside a small church. The only point of interest here is a bronze sculpture of a house painter, purported to be the confidante of Robespierre, although a website denounces this as untrue and nothing more than a posthumous prank.

Being nearer to where I was I took the Metro to Pere Lachaise and spent time looking for tombs of people whose works I admire. Thanks to a map I downloaded online and the interesting fact that there are good wifi hotspots in cemeteries (future grantees take note), I was able to maneuver around the vast hilly area with its remarkable mix of sepulchers, mausoleums and funerary sculptures from the 19th century. Thus I found the graves of the painter Gericault (with an effigy and reliefs portraying his best known works such as The Raft of the Medusa), Chopin (with an angel on top and a medallion in marble of his profile), the artist Arman, the poet Victor Noire and his famous bronze effigy (depicting a fallen young man with a curious erectile bump that visitors have worn off by touching), Amedeo Modigliani and his wife Jeanne (the latter committing suicide the day after his death and lastly, out of curiosity, Jim Morrison, of The Doors. On my way out, I discovered the sepulcher of Trinidad Pardo de Tavera, a prominent scholar of Philippine history and culture.

The following day I struggled to find Cimeterie Picpus, the site of mass graves of the 1300 victims of the guillotine but found it closed. Frustrated, I went to three others, Montmartre, St. Vincent and Passy where I spent some hours for the rest of the day. At Montmartre I paid my respects at the tombs of Degas and Dumas (shown with an effigy of the writer in repose, sadly damaged). This cemetery has a number of very interesting funerary statuary that I could not but take photographs. Wifi was so good near the sepulcher of Degas that I was able to talk on video via Skype to Jun Villalon, gallerist of Drawing Room in Manila and Singapore. When he saw where I was, he commented that I was making a pilgrimage. Probably so but not inaccurate. At nearby St. Vincent, under the shadow of the dome of Sacre Coeur, I found the tomb of painter Maurice Utrillo. Then later than day I took the Metro to Trocadero and found the graves of Manet and Debussy in Cimetiere Passy. This small cemetery also had very interesting sculptures, among which are a bronze Rodin portrait and a St Jeane that was remarkable for its sensuous form, despite the context of a holy place. But what moved me as a sculptor was the massive wall sculptural group commemorating the French soldiers of the First World War of 1914-1918. Their austere forms understated the pathos of grief and remembrance, and highlighted the sense of tragic dutifulness - of the burden of going to war. Ironically the players of this Grande Guerre were in fact initially cheerful, as they brought their idealism and youth to the front, only to be destroyed by the dreary trenches and experimental use of chemical weapons and tanks. It reminded me of a young French sculptor, Henri Gaudier-Brezska, who fought and died during this war, but not without losing his sense of aesthetic as he carved small sculptures in stone during the intervals of non-combat. He fought the war with sculptures in his pockets. A brilliant life, and indeed he was called a Savage Messiah by HS Ede, a British writer who did his biography.

I continued my Dead week theme with a return to Montparnasse on Thursday and a much-delayed visit to Basilique St. Denis the day after. In Montparnasse I again passed by the grave of Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir and found the tomb of Brancusi. I took photographs once more of numerous statues and began a comparative listing of characteristics from each cemetery. This cemetery for instance has a Nikki de St.Phalle sculpture of a giant cat in tiles and concrete and another abstract metal piece representing a bird in flight, in contrast to the Romantic bronzes that show weeping women in shrouds and with Baroque overtones of glorious afterlives.

At St. Denis, at the crypt and before the stone effigies of the Kings, I found the acme of my week. At the rear of the huge basilica (accessible with a ticket of 7,50€) lies a number of carved representations of the dead royals, mostly in marble, eternally resting with their eyes gazing upwards, and often carrying their symbols of power. But I explored the crypt first, which houses the tomb of St. Denis, claimed to be the first archbishop of Paris and martyred (beheaded) around 250AD. Being trained in santo-making I was quite taken with the representation of this martyr: dressed in a bishops garment, but with his decapitated head in his hands. One reproduction of a painting even presented him with blood squirting from his severed jugulars. But what was remarkable to know was this site was a pilgrimage place since the 5th century and was one of the most powerful Benedictine abbeys in the Middle Ages. It became a necropolis of kings and queens from the 6th century onwards. In the 12 century Abbot Suger of Saint Denis made the former abbey into an example of early Gothic art, but it was in the12th century that the church received its present look and after deteriorating through wars and the revolution it was restored by Viollet-le-Duc in the 19th century. If I may comment, I have not seen any church this ancient back home.

In the crypt I found the tomb of St. Denis, the symbolic center of this basilica, and met some French school children being regaled by a wiry teacher with stories of how St. Genevieve, patroness of Paris, had asked Hannibal to spare the city. The tomb, of carved stone, lies empty, but a projected image of the saint marks where his body lies underground (a nice solution by way of signage) and surrounding this area are more sarcophagi, but beyond a grate and gate and inaccessible to all. In the adjacent areas lies other crypts where princes and kings where once interred.

Emerging from the crypt and into the necropolis were the stained-glass illuminated chapels that held around 70 recumbent statues of the royals. I was attracted to a particular chapel, named in honor of a St.Hilaire. With my santomakers hagiography I have not encountered such a saint before, an a namesake at that.

What I paid close attention to are the sculptures, taking photos of interesting details, such as the way hair is carved, or what animals are placed at the feet of the kings, mostly dogs. One unknown royal was curiously carved in black stone and at her feet are three snarling dragons. While doing documentation I had an insight, a confirmation of a suspicion really, that the models and prototypes that my santero uncle had shown me when I was 15 were of the Gothic style. And it was this style that I preferred over Baroque or Neoclassical santos (which I thought were a bit superfluous). The austere, block like and linear forms of the funeral statuary of this necropolis echoed those of my own aesthetic sensibilities. In fact, I began to wonder if this is my very own "French connection". Here, in the context of a medieval building, I began to understand the origin of the images that were my models of instruction in wood carving. The ancestry of my sculptural practice may really be the Gothic, and hence my attraction to the arts of the Medieval period.

Hence, in conclusion to my Dead week, I have gained several insights and this thematic approach has somewhat given much-needed coherence to my exploration of Paris. I have learned a great deal about the changing attitude of the French towards the dead: from the open eyed statues of the kings at St. Denis as a way of looking upward in anticipation of Eternal Life, to the eternal postures of grief of funeral statuary in Pere Lachaise, to the simple, understated tombs of great men like Sartre and Brancusi bearing nothing except names.

Sartre has said in one of his stories that death is a wall. There is nothing behind it, nor one should even care what is beyond this. But death does not belong to the moribund, to the dying. It belongs as a fact, to those who left behind. Simone de Beauvoir eulogized the passing of her life long partner Sartre by saying "his death separates us, but my death will not reunite us." She was right, though. Our lives might be within the horizon of our freedom, but when we have left, our death will only have meaning if and when those who survive us, remember.

And that is what cemeteries, necropolises, ossuaries and monuments are for: an effort to remember.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed